How an 18-Year-Old Is Prototyping Real Solutions for Homelessness and Climate Impact – with video

Ribal Zebian

I often hear about someone—or some company—that has a new idea to improve, restart, or outright fix a problem in construction. Every time I hear that word, new, I can’t help but smile. Not because I’m cynical (well, not entirely), but because “new” has become one of the most overused words in our industry. It’s so overused that the moment it’s spoken, my mind immediately jumps to the same two questions:

How long will this take to fail?

And on rare, glorious occasions: Will this actually work?

Construction has a long memory. It may not always look that way, but it remembers. It remembers what worked, what didn’t, and what sounded brilliant in a conference room but died quietly on a production line somewhere between Tuesday morning and the first broken fastener. That’s why “new” is such a loaded word. Most of the time, it isn’t really new at all.

Over the years, I’ve noticed that new ideas in construction tend to fall into two very distinct categories. Understanding which category you’re dealing with can save you a lot of time, money, and embarrassment.

The first type of “new” usually comes from someone already inside the industry. These ideas are often introduced with genuine enthusiasm and good intentions. The person presenting it truly believes they’ve stumbled onto something groundbreaking.

In reality, what they’ve created isn’t new—it’s an evolution.

That’s not a bad thing. In fact, most real progress in construction comes from evolution, not revolution. Someone sees a problem, remembers ten years of dealing with that problem, and figures out a slightly better way to handle it.

Take automated manufacturing equipment as an example. A machinery manufacturer announces a new automated table with built-in AI responders that can detect imperfections down to one millimeter. That sounds impressive—and it is. But it isn’t new. It’s an improvement. A meaningful one, perhaps, but still part of a long, steady march toward better accuracy, better consistency, and fewer human errors.

The real questions don’t start with Is it new?

They start with:

Will it survive the production line?

Because that’s where construction ideas go to be tested. Not in brochures. Not in PowerPoint decks. And certainly not in press releases. They get tested at 6:30 a.m. on a Monday when the line is already behind schedule, the crew is short two people, and someone just spilled coffee on the control panel.

Even if the technology works exactly as promised, there’s another hurdle: Will anyone actually want it?

Does it save time?

Does it reduce labor?

Does it lower costs or increase margins in a way that makes sense?

If the answer to those questions isn’t clear, even the smartest improvement will struggle. Construction doesn’t reward cleverness for its own sake. It rewards results.

The second type of “new” is far more entertaining—and far more dangerous.

This version usually comes from someone with experience in a similar industry. Automotive. Aerospace. Advanced manufacturing. Sometimes tech. They look at construction and immediately see inefficiency, fragmentation, and chaos. And they’re not wrong.

The problem is what comes next.

They become convinced that their idea—borrowed, adapted, or reimagined from their previous industry—is going to revolutionize offsite manufacturing. They pitch investors. They raise capital. They land glowing write-ups in industry publications. They appear on podcasts, host webinars, and speak confidently about “transforming construction as we know it.”

All of this often happens before they have a finished product. Sometimes before they have a working prototype. Occasionally before they’ve spent more than a week inside an actual factory.

And for a while, it works. The buzz builds. The language gets bolder. Words like disruption, scalability, and game-changing get tossed around like confetti.

Then something truly remarkable happens.

They meet the Demons of Construction.

Construction is polite at first. It lets you talk. It lets you demo. It lets you believe.

Then it asks for results.

Not someday. Not after the next funding round. Not once the market “catches up.” It wants results that are effective, affordable, and scalable—right now. Results that work on real factories, with real people, under real constraints.

This is usually the moment when things start to unravel.

The solution doesn’t integrate as easily as promised.

The learning curve is steeper than expected.

The costs don’t line up with the savings.

The factory managers nod politely and never call back.

And slowly, quietly, the once-promising startup begins to fade. Fewer posts. Fewer appearances. Eventually, silence. Another idea chewed up and digested by an industry that has no patience for theory without proof.

It’s not cruelty. It’s survival.

Every time I hear about a new process or a new idea, I ask myself a simple question:

Who is this coming from?

Is it someone inside the industry, whose idea has at least been shaped by experience? Or is it someone looking at construction from the outside, convinced they’ve found the missing piece we’ve all somehow overlooked?

Either way, I smile. Because I know the Demons of Construction are already waiting.

Who are they? I don’t really need to tell you. If you’ve been in this business for any length of time, you already know them.

They show up as budgets that never stretch far enough.

Schedules that laugh at optimism.

Labor shortages that refuse to be solved by software alone.

Codes, inspectors, logistics, weather, transportation, and human nature.

They aren’t villains. They’re realities. And they don’t care how elegant your idea looks on paper.

If you’re new to construction, you’ll meet them soon enough. Usually right after you try to implement your first “simple” improvement.

None of this means innovation is pointless. Far from it. Construction needs better tools, smarter systems, and fresh thinking. But the ideas that survive tend to share a few traits.

They respect the complexity of the industry.

They solve one real problem instead of ten imaginary ones.

They prove their value on the floor before shouting about it online.

And most importantly, they understand that construction doesn’t need miracles. It needs improvements that work on a bad day, not just a good one.

So the next time someone tells you about a new idea that’s going to change everything, listen politely. Ask a few practical questions. And watch closely.

If it survives the Demons of Construction, you might just be witnessing real progress. If not, well—there will always be another “new” idea coming along next week.

And I’ll probably smile at that one too.

Written by Gary Fleisher—industry writer, consultant, and longtime voice of offsite and modular construction.

Watching my 14-year-old grandson — a Gen Alpha kid who somehow squeezes four lifetimes into one — has completely changed the way I look at the future of our industry. This is a young man who taught himself to weld in his garage, sketches plans and builds backyard structures for fun, repairs small engines for neighbors, runs a lawn care business he started at age 10, and still pulls off good grades in high school.

Not because someone told him to. Not because there’s a curriculum for it. But because he wants to understand how things work — and how to make them better.

And watching him led me to one question that our entire industry needs to start asking:

How do we bring more young people into construction and offsite manufacturing, not just as skilled workers… but as skilled entrepreneurs?

Because this is a different segment of labor — a desperately needed one. Factories need line workers, yes. But they also need doers who become thinkers, and thinkers who become founders. They need the next generation of subcontractors, installers, innovators, factory owners, and problem-solvers who look at inefficiency and say, “I can fix that.”

If we fail to develop that side of the workforce, we won’t just be short on talent — we’ll be short on leadership.

So let’s talk about how we grow that entrepreneurial spark from the ground up.

Here are my suggested “7 Steps to Entrepreneurship”

Step One: Build Ownership Thinking Early

You can’t learn ownership by watching someone else clock in. Ownership has to be experienced, and it should start long before a young person steps onto a jobsite.

Trade programs still teach people to work for a boss, not be one. Every construction tech program should build in a mini-business pitch, a pricing exercise, or a project that requires estimating, scheduling, and customer communication.

Entrepreneurship doesn’t begin with a loan application — it begins with a mindset. And the earlier we cultivate it, the stronger it grows.

Step Two: Apprentice in Business, Not Just a Trade

Traditional apprenticeships teach skills; entrepreneurial apprenticeships teach systems. Pair every apprentice with an owner, estimator, or operations lead once a month. Let them see the business side — the bids, the budgets, the surprises, the stress, the strategy.

If you want someone to eventually run a company, they need to understand far more than how to build the product. They need to understand how to keep the doors open.

Step Three: Create Micro-Entrepreneurship Opportunities

Gen Z and Gen Alpha don’t want to wait a decade for responsibility — they want it now, and they thrive when they get it.

Factories could create “Own Your Crew” starter programs. Trade schools could host small-business building competitions. Communities could support student-run micro-crews doing repairs, ADU prep work, yard structures, and real paid projects.

Small opportunities build real confidence — and confidence builds founders.

Step Four: Match Them With Mentors Who Have Scars

The best entrepreneurship teachers aren’t professors — they’re people who survived mistakes. Retired builders, former GMs, and veteran factory managers should be the backbone of a new mentorship movement.

If you’ve made payroll in a slow month or rebuilt a business after a bad year, you can teach more than any textbook ever will. And young people want real talk. They want the truth, not the brochure.

Step Five: Redefine Innovation for This Generation

Young people think innovation means robotics, AI, or 3D printing. Sure — those matter. But innovation in our industry also looks like shaving a day off a schedule, redesigning the flow in a factory, improving logistics, or managing installs smarter.

Show them that entrepreneurship in construction is often about improving a process — not inventing a gadget. When they understand that, they start looking for opportunity everywhere.

Step Six: Teach Tech With Purpose

The future entrepreneur in our industry will use AI as casually as a tape measure. BIM won’t be “specialized software.” CRMs won’t be “nice to have.”

If we want tomorrow’s builders to run successful companies, we must train them to think digitally. Not because tech replaces knowledge — but because tech multiplies it.

When a young builder understands both construction and digital tools, they become unstoppable.

Step Seven: Celebrate Young Founders Like Rock Stars

We highlight machines, robots, and giant factories — but not the 19-year-old who launched a small CAD studio or the 22-year-old who started a framing crew with two friends.

If we want more entrepreneurs, we need to show entrepreneurs. Every story of a young builder-founder is a spark. And sparks create momentum.

THE BIG PICTURE

We cannot solve the labor crisis by training workers alone. We also need to train owners, leaders, creators, problem-solvers, and risk-takers.

Factories will always need line workers. But the industry will collapse without the innovators who hire those workers, refine the processes, and build the companies that move offsite construction forward.

The future belongs to the young people who don’t just want jobs — they want ownership. They want autonomy. They want to build something that’s theirs.

Our job is to give them the blueprint — and then get out of their way.

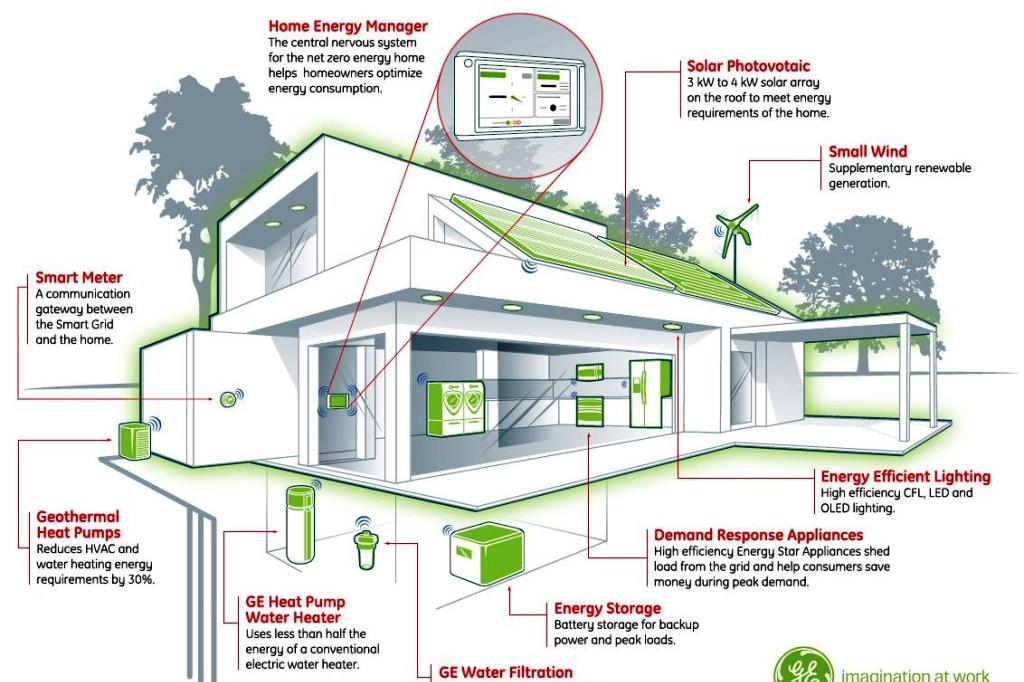

Why climate-smart design is the next big shift for modular and tract builders

For decades, homebuilding has followed a simple pattern: design the house, then make it comfortable by adding heating, cooling, and insulation. But today’s builders — especially in modular and prefabricated housing — are flipping that logic upside down. Instead of forcing comfort onto a design after the fact, they’re starting with the climate itself.

Welcome to the growing world of bioclimatic design — an approach that makes a home work with its environment instead of fighting against it. It’s one of the most promising movements in construction, and it’s finding a natural home in prefabricated housing, where precision and efficiency already lead the way.

At its core, bioclimatic design means shaping a home around the conditions of its specific location. It’s not about fancy technology or high-priced materials — it’s about common sense, refined by science.

A bioclimatic house takes into account the sun, wind, temperature, humidity, and even local vegetation. The goal is to reduce the need for artificial heating and cooling by designing a structure that naturally stays comfortable all year long.

Think about it this way: a home in Phoenix shouldn’t be designed the same way as one in Portland. In the desert, you want deep overhangs, light-colored walls, and narrow windows that limit direct sunlight. In a cooler climate, you want the opposite — broad south-facing windows that let the sun pour in during winter, with trees or shading devices to block it during summer.

By understanding these basic principles, a designer can make a home that consumes 30 to 60 percent less energy without relying on expensive mechanical systems. That’s bioclimatic design at work.

Prefabricated and modular homes are built in controlled environments, where precision is everything. That makes them ideal for bioclimatic strategies.

Factory-built homes can be oriented on the lot exactly as designed — with windows, shading, and insulation tailored for the region before they ever leave the production line. Walls can be built with airtight seams, triple-glazed windows can be fitted perfectly, and roof overhangs can be manufactured to precise angles that optimize solar gain.

Unlike site-built homes that depend on varying craftsmanship, prefabricated homes ensure that each energy-saving detail is executed exactly as planned. The repeatability and quality control of the factory environment give bioclimatic design a powerful advantage.

Even small changes at the design stage — like window placement or the choice of exterior materials — can make a big difference when applied consistently across dozens or hundreds of homes.

Here’s where things get even more interesting. Bioclimatic design isn’t just for custom eco-homes or experimental green projects. It’s starting to show up in mainstream housing developments, where efficiency now meets profitability.

Large tract builders are learning that climate-sensitive designs can lower construction costs and boost buyer appeal at the same time. By aligning floorplans, rooflines, and window placements to suit regional climates, builders can create entire neighborhoods that stay cooler in summer and warmer in winter — using less energy and fewer mechanical systems.

For example, a tract builder in Texas might orient homes to capture prevailing breezes, while one in Colorado might design south-facing windows with longer roof overhangs to provide winter warmth and summer shade. These are small tweaks with big payoffs.

The result? Lower monthly utility bills for homeowners and higher long-term satisfaction — two selling points every builder wants to advertise.

Many modular home factories are beginning to integrate bioclimatic design into their product lines. Some are hiring sustainability consultants to model how their standard floorplans perform in different regions. Others are offering “climate packages” that adapt wall thickness, insulation type, and glazing for specific climates — the same way car manufacturers offer packages for cold-weather or desert driving.

A factory that understands bioclimatic principles can pre-engineer homes that perform exceptionally well across climate zones, giving them an edge in both residential and commercial projects.

For example, modular factories in the Southeast are using deep eaves, reflective roof coatings, and vented cross-breezes to handle humidity, while factories in the North are focusing on passive solar design and high R-value wall systems. The shift is subtle but significant: modular construction is no longer just about speed and cost — it’s becoming about climate performance.

The homebuilding industry has spent the past decade chasing “smart home” technology — thermostats that learn, lights that adjust, and appliances that sync with your phone. But bioclimatic design is smart in a different way.

It doesn’t depend on software updates or electricity. Instead, it uses timeless principles that have worked for centuries: sun paths, wind direction, and thermal mass. Ancient builders understood these things instinctively — from adobe homes in the Southwest to stone cottages in Europe — and we’re finally rediscovering their wisdom.

The modern twist is precision. With today’s digital design tools, offsite builders can simulate how sunlight will strike a wall on any day of the year, or how a breeze will pass through a courtyard. That information turns into measurable savings when the home is built.

There’s also a clear economic argument. Energy-efficient homes don’t just reduce bills — they sell faster and hold value longer. Buyers today are increasingly aware of energy costs and environmental impact. When builders can show that a home’s comfort and efficiency come from its design, not just its equipment, it builds trust and distinction in a crowded market.

In fact, many major homebuilders are already rebranding their developments around “climate-smart living” or “naturally efficient design.” The message resonates because it’s practical, not political. It’s about comfort, savings, and good design — values that appeal across demographics.

As more states update their energy codes and municipalities push for lower-carbon building methods, bioclimatic design will move from an optional feature to an industry standard. For modular factories and tract builders, it’s a rare win-win: a design philosophy that improves both environmental performance and customer satisfaction.

The housing of the future won’t rely solely on bigger HVAC systems or high-tech gadgets. It will rely on smart design that responds to nature — and prefabrication is the perfect vehicle to deliver it.

My Final Thought:

Bioclimatic design isn’t a trend; it’s a return to common sense. It’s about learning from the sun, the wind, and the land beneath our feet. And in a world where every kilowatt and every dollar matters, the smartest homebuilders — whether they’re running massive tract operations or modular factories — are realizing that the best way to fight the climate is to build with it.

What would really happen if you ask your entire team how they’d restart your offsite construction company from scratch — and then tell them you’re ready to do it.

Picture this.

You gather everyone in your offsite construction company—managers, drafters, production crews, even the guy who somehow always fixes the nail gun with chewing gum and a smile. The room is buzzing with quiet curiosity, waiting for the usual safety talk or production update.

Instead, you drop this bomb:

“If I were to start this business over again from scratch, what changes would you make?”

At first, they blink. Then it happens.

It starts with a few brave souls. Someone points out that the scheduling software causes more chaos than clarity. Another says the wall panel line was never set up for efficiency, just jammed into whatever space was left. A crew lead admits that training new hires is like tossing them in the deep end and hoping they float.

Suddenly, everyone’s talking. Not complaining—building.

Ideas fly. Frustrations finally see daylight. People who’ve quietly tolerated the daily grind are sketching out better ways to do it. You can almost feel the oxygen come back into the room.

For a moment, it’s electric.

And then… you say it.

Silence.

The air shifts from excited to nervous in a heartbeat.

Because now it’s real.

They picture their jobs changing—or disappearing. They picture production slowing down. They wonder who’s going to be blamed for the old way and who will be left standing when the dust clears.

And just like that, the enthusiasm that lit the room like a sparkler suddenly feels like a wildfire creeping toward their desks.

Change sounds exciting… until it sounds like risk.

Here’s where you find out what your company is really made of.

In a high-trust shop, your crew will lean in. They’ll want to help shape the future. They’ll volunteer to pilot new processes, rethink old habits, and prove that they’re part of the solution.

But in a low-trust shop, fear takes over. People retreat. They start quietly thinking about their résumés. Innovation dies in the same meeting where it was born.

You can’t bulldoze fear with enthusiasm. You have to build trust first, brick by brick.

Handled well, this moment can be a turning point. A company reborn from the inside out.

Handled poorly, it’s just another big speech no one believes, followed by a slow fade back to “the way we’ve always done it.”

The difference comes down to leadership.

Not the chest-thumping kind—the listening kind.

The kind that turns those raw, honest answers into an actual plan. A plan where employees lead the charge, not just watch from the sidelines waiting for the next round of chaos.

Asking “What would you change if we could start over?” can be the boldest, bravest question a factory owner ever asks.

But if you’re going to light that fuse, you’d better be ready to guide everyone through the explosion—and into something better on the other side.

Because this isn’t about tearing down a company.

It’s about finally giving everyone the chance to build it right.

If you believe it’s time for your factory to make some changes, Bill and I are here to help.

Bill Murray, experienced Advisor to the Offsite Construction Industry

Sign up for a Free 30-minute Video talk about your company’s future options.

After thirty years of walking into a modular factory, I ask myself the same question: Is this place truly a small business, or is it more like a hobby that just happens to produce a few homes? The answer isn’t always as obvious as it seems. Production volume, financial planning, and even intent all play a role in defining what a factory really is. And when it comes to survival, the difference is everything.

When a modular plant is building three or four ranch homes or two or three two-story homes each week, it’s operating like a small business. Dozens of employees are on the payroll, materials are moving in and finished homes are rolling out, and the line is humming most days. The factory is carrying the weight of regulatory compliance, inspections, taxes, and supply chains while meeting the demands of multiple builders or developers.

At this scale, the numbers can work. Volume spreads overhead, and even modest margins can start to add up. If the owners have a solid business plan and a marketing strategy that keeps builders in the pipeline, the factory has a legitimate chance to grow. But here’s the catch: without those plans in place, the factory quickly stalls. Volume alone doesn’t guarantee survival. Without discipline, focus, and the ability to adapt, even a small business factory finds itself struggling to cover costs and retain talent.

Now picture a plant producing just three or four homes a month. On paper, it looks like a business: the company is licensed, workers are employed, and homes are being built. But in practice, it operates more like an expensive hobby.

The economics simply don’t work at this level. The insurance bill, the mortgage on the building, the utility costs, and the payroll all arrive on time, regardless of how many homes ship out that month. When the line only moves a few times in thirty days, the very advantage of modular construction—efficiency through throughput—disappears. Unless the homes are luxury builds with enormous markups, margins collapse, and the operation limps along as little more than a workshop.

What makes the difference between a business and a hobby isn’t just production numbers. It’s the plan behind them. Factories that succeed know their markets, secure commitments from builders before the first panel is cut, and put as much energy into sales and marketing as they do into production. They plan for years ahead, not just for the next few orders.

The ones that fail rely on hope. They assume that orders will appear if the product is good enough. They lean too heavily on a single customer. They confuse passion for planning and enthusiasm for strategy. I’ve seen more than a few of these so-called factories close their doors within two years, and too many others plateau because the owners believed that production alone was the path forward.

So here’s the question worth asking: if a modular factory is producing just a few homes each month, is it really a business—or is it a hobby dressed up as one? And more importantly, can either model survive long-term without a clear business and marketing plan to push beyond the startup phase?

The brutal truth is this: without a strategy, the size of the factory doesn’t matter. Whether you’re producing four homes a week or three a month, the clock is already ticking, and it always runs out faster than you think.

If your factory fits the hobby model today, what’s your plan for turning it into a real business tomorrow?

Bill Murray, experienced Advisor to the Offsite Construction Industry

Bill and I are here to help. Sign up for a Free 30-minute Video talk about your company’s future options.

The hum of saws, the clatter of hammers, and the laughter of young voices filled the Whitbeck Construction Education Center in Gansevoort, New York this summer. What might sound like just another week in the life of a bustling construction shop was, in fact, something far more extraordinary: the Northeast Construction Trades Workforce Coalition (NCTWC), in partnership with Whitbeck Construction and WSWHE BOCES, proudly wrapped up another highly successful Girls Construction Summer Camp.

For two week-long sessions, from July 21–25 and July 28–August 1, middle school girls in grades 6 through 8 discovered that construction isn’t just about tools and materials—it’s about confidence, teamwork, and a future filled with possibilities.

Nationwide, only 11% of the construction workforce is female. That number speaks volumes about the hurdles young women face in imagining themselves in hard hats and steel-toe boots. The Girls Construction Summer Camp is designed to change that narrative. By giving girls hands-on opportunities to learn, build, and explore, the camp helps dismantle stereotypes and opens the door to careers too often overlooked.

“This camp is all about opening doors and driving awareness,” said Doug Ford, co-founder and President of NCTWC. “Every year we see the transformation—girls who come in unsure of themselves leave with confidence, skills, and the realization that they can succeed in this industry. That is the heart of what this program is about.”

Over the course of the camp, participants didn’t just observe construction—they lived it. They learned how to safely handle tools, apply math and science in practical ways, and build projects they could proudly carry home: toolboxes, benches, even Adirondack chairs.

Beyond the workshop, the camp extended learning into the community. Construction site visits and business field trips gave campers an inside look at what a future in the trades could mean, from project management to skilled craftwork. For many, it was the first time they had ever imagined themselves not just holding a hammer, but leading a team or running a job site.

And then there was the Construction Olympics. Equal parts fun and skill test, the event had campers working together to showcase what they’d learned—sparking both camaraderie and confidence.

The Girls Construction Summer Camp is just one example of the Northeast Construction Trades Workforce Coalition’s growing impact. Founded by Doug Ford and Pam Stott (formerly of Curtis Lumber), the coalition became a 501(c)(6) not-for-profit in 2023 with a mission to strengthen the skilled trades workforce pipeline. By partnering with businesses, educators, and industry leaders, NCTWC is building programs that prepare tomorrow’s workforce today.

Since its founding, the coalition has rapidly expanded its outreach, establishing itself as a hub for workforce development in the region. The Girls Camp shines as a testament to what can be achieved when industry and education come together with a shared purpose: to inspire and equip the next generation of builders.

For the girls who participated, the impact goes far beyond the projects they built or the skills they practiced. Many walked away with something even more valuable: the belief that they belong in construction. That realization could be the spark that changes the trajectory of their education, their career path, and, ultimately, the industry itself.

The Girls Construction Summer Camp is more than a summer program. It is a statement of possibility, a reminder that when opportunity meets encouragement, new futures can be built. The Northeast Construction Trades Workforce Coalition is not only filling a labor need—it is rewriting the story of who gets to wear the hard hat, hold the blueprint, and lead the team.

And if this summer’s camp is any indication, the future of construction looks brighter, stronger, and far more inclusive than ever before.

Imagine this: 42 sleek, modern micro‑homes quietly springing up in East Chattanooga—affordable, sustainable, and community‑centered. Welcome to Valentina Estates, the first project of its kind in Tennessee, spearheaded by none other than former pro basketball player Rashad Jones‑Jennings. A true hometown hero, he’s swapping arenas for architecture, and the results are stunning.

Rashad Jones‑Jennings

At a $12 million investment, Jones‑Jennings is building each home for under $300,000—a sharp contrast to Chattanooga’s average home price of roughly $326,279. These aren’t just smaller homes; they’re thoughtfully designed spaces meant to bring dignity and affordability to buyers who’ve “done everything right”—yet still struggle to reach that next price tier.

“I grew up on the west side,” he shares, “and I don’t think that model works. You put everybody that’s in survival mode in one area.” For Jones‑Jennings, this isn’t gentrification—it’s revitalization. He’s not tearing down Grandma’s house and pushing neighbors out. Instead, he’s upgrading the area’s infrastructure and preserving its character.

Locals are understandably mixed. Some worry about increased traffic, while others feel hopeful—finally, a development that speaks to the community, not over it. “We gathered the neighborhood up… we talked about what it would actually do for the community,” one resident said.

Chattanooga officials clarified that the city doesn’t subsidize Valentina Estates—it’s market‑rate housing priced at a level that someone earning 80% or less of Area Median Income could manage, spending no more than 30% of their income on housing.

But this is bigger than bricks and mortar. Jones‑Jennings sums it up best: “I wanted to see the people around me win as well.” And if all goes to form, families could be moving in as early as 2026.

Valentina Estates is the perfect blend of purpose and practicality—a project built by a local legend who knows the neighborhood because he is the neighborhood. With affordability, design, and community at its core, this micro‑home community may just be the blueprint Chattanooga—and cities like it—needs.

This article is based on “Chattanooga gets ready for first micro‑home community, led by former pro basketball player” by Sarah Hower for WTVC NewsChannel 9

Designing and building a modular factory has never been more exciting—or more accessible. In fact, it seems like every month a new team of consultants pops up, ready to help bring someone’s offsite vision to life. These firms range from solo operators to full-service companies with slick presentations, clever branding, and blueprints to make your dream factory rise from the ground with robotic arms, digital twin models, and gleaming production lines.

But here’s the question too few dreamers ask before they start spending real money:

Does your dream actually have a chance of becoming a sustainable business?

Most consultants you hire to design and build your factory will do exactly what you pay them for—design and build your factory. What they won’t do is tell you whether that factory has even a fighting chance to turn a profit. That’s not in their scope. Their job is to make your vision a physical reality. But maybe—just maybe—that vision needs a reality check before anyone draws up a floorplan or collects a deposit.

Let’s say five developers have promised they’ll buy from your future factory. That’s a nice start, but have you asked yourself: what happens after their first orders? Is there a long-term market for your product? Do you have a plan for when interest rates spike or city zoning shifts or a promised housing development gets delayed by a year?

Too many first-time factory founders get swept up in the excitement of creating something physical and forget the equally important (and less glamorous) business side:

We live in a time where you can simulate your entire factory with AI before you ever pour a slab. Yet most founders skip this step. Why? Because they’re busy talking to consultants about line layout, equipment purchases, and vendor contracts.

The smart entrepreneurs—those who last longer than the factory grand opening—start by running simulations, talking to real-world advisors, checking market saturation, and analyzing their pricing model. Only then do they bring in the factory builders.

Consultants are often paid to fulfill a scope of work—usually something tangible like design, buildout, or startup support. When they’re done, they move on to the next client. And they’re often already working the pipeline looking for their next big fish.

Advisors, on the other hand, aren’t there to build your factory—they’re there to help you build a better business. They ask the hard questions. They push you to examine your assumptions. They may even tell you your idea needs more work before you go any further. That kind of honesty can save you hundreds of thousands of dollars.

It’s not that consultants are bad. Many are excellent. But hiring one before doing your strategic homework is like building a luxury home on unstable ground. The framing may be perfect, but it won’t last if the foundation can’t support it.

Here’s the question every aspiring modular factory founder should ask:

If I build this, will it survive long enough to make a profit—or am I building something beautiful that no one will need in three years?

With the explosion of modular and offsite factories opening in the next few years—especially in the “affordable housing” sector—you have to ask yourself: how many will still be standing, and thriving, by year four?

It’s okay to dream. In fact, we encourage it. Just make sure someone is helping you connect that dream to a viable, profitable plan—before the consultants arrive with floorplans and equipment lists.

If you want to talk to someone who can help you ask the right questions first, Offsite Innovators is here. The right advice at the right time could be the difference between a dream realized and a factory failure.

When you finish your morning espresso, the last thing on your mind is what happens to those spent coffee grounds. Most of us assume they vanish into the trash, destined for landfills. But what if that leftover caffeine kick could help build your next home or office building? Thanks to groundbreaking research at Swinburne University of Technology in Australia, that’s no longer a wild fantasy — it’s a promising new reality.

Swinburne’s team, led by Dr. Yat Wong, has unveiled an innovative process that turns used coffee grounds into sturdy, low-emission bricks. Their work not only promises a greener alternative to traditional clay bricks but also offers a creative solution to one of the world’s most overlooked waste problems.

Globally, we produce about 10 billion kilograms of spent coffee grounds each year. Most of this aromatic byproduct ends up in landfills, where it releases methane — a greenhouse gas significantly more potent than carbon dioxide. Recognizing both the environmental threat and the untapped potential, the Swinburne team set out to transform this waste stream into something valuable.

The process begins by partnering with local coffee shops to collect the used grounds directly from espresso machines. These grounds are then combined with natural clay and an alkali activator to create a unique mixture. Unlike traditional bricks, which require firing at temperatures around 1,000 degrees Celsius, these coffee bricks are cured at just 200 degrees Celsius. This drastic reduction in heat slashes electricity-related carbon dioxide emissions by up to 80% per brick.

But sustainability isn’t the only win here. Swinburne’s coffee bricks are faster and cheaper to produce than conventional clay bricks. The lower curing temperatures mean factories consume less energy, cutting production costs while reducing their environmental impact. Plus, each brick effectively locks away what would otherwise be a potent source of methane.

From a performance standpoint, the results are equally impressive. According to Swinburne, these bricks exceed Australia’s minimum construction strength standards by roughly double. That means they aren’t just an eco-friendly novelty — they’re a genuine contender for mainstream construction applications.

The innovation has already taken a big step toward real-world use. In a move that signals serious commercial potential, Swinburne recently signed an intellectual property licensing deal with Green Brick, a company focused on sustainable building materials. This partnership will help scale production and move these coffee-infused bricks from the laboratory into the marketplace. Soon, we may see office buildings, apartment complexes, and even single-family homes built with the remnants of our morning brew.

This development is part of a broader global push to find circular economy solutions within construction — a sector that accounts for nearly 40% of global carbon emissions. By finding creative ways to reuse materials, researchers and entrepreneurs are reshaping what our buildings are made of, and how we think about waste.

Beyond environmental benefits, this project also offers a compelling economic argument. Coffee shops gain a sustainable disposal solution, brick manufacturers save on energy costs, and developers can market their projects as green and forward-thinking. It’s a rare case where environmental responsibility and business efficiency go hand in hand.

From Coffee to Concrete: Turning Everyday Waste into Tomorrow’s Building Material

As cities worldwide grapple with the urgent need to cut emissions and move toward net-zero goals, innovations like Swinburne’s coffee bricks show us that solutions can come from unexpected places — even your local café. Each espresso, latte, or flat white you enjoy could contribute to the walls of future homes and offices, closing the loop on a daily ritual most of us take for granted.

For now, the next time you sip your morning coffee, imagine a future where that leftover sludge isn’t just waste but the foundation of a more sustainable world. With visionary research and practical partnerships, Swinburne University of Technology has turned an everyday habit into a bold step forward for construction — one cup at a time.